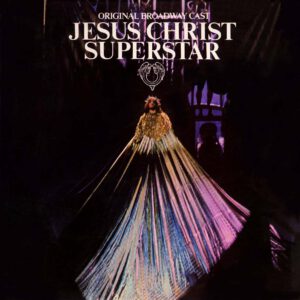

Artwork

Cast

NOTE: Please note that there were many replacements during the course of the show, which was par for the course in a Tom O’Horgan production; just ask any former cast members of Hair. For example, a fan on the 2012 Broadway revival’s Facebook page reports: “Ben Vereen… was injuried (sic) and replaced by seveal (sic) Judases. I gave a cast member a copy of an early Playbill and by the sixth month, three people had played Judas.” Therefore, if you see any differences in this cast list from other lists of the OBC reported elsewhere, please note that this is the cast as of recording, courtesy of the liner notes for the 2003 Decca Broadway CD release.

Jesus of Nazareth…………Jeff Fenholt

Judas Iscariot…………Ben Vereen

Mary Magdalene…………Yvonne Elliman

Pontius Pilate…………Barry Dennen

King Herod…………Paul Ainsley

Simon Zealotes…………Samuel Wright

Caiaphas…………Bob Bingham

Annas…………Phil Jethro

Peter…………Michael Jason

Priests…………Steven Bell, Alan Braunstein, Michael Meadows

The Chorus…………Robert Barnes, Edward Barton, Ferne Bork, Celia Brin, Dennis Buckley, Kay Cole, Dennis Cooley, Charlotte Crossley, Denise Delapenha, Pi Douglass, Marsha Faye, Tony Gardner, Michael Jason, Melvin Laszczynski, Clifford Lipson, Laura Michaels, Anita Morris, Nathanial Morris, Ted Neeley, Cecelia Norfleet, Janet Powell, Linda Rios, James Sbano, Peter Schlosser, Bonnie Schon, Tom Stovall, Paul Sylvan, Margaret Warncke, Willie Windsor, Samuel Wright, Kurt Yaghjian

Orchestra

Randall’s Island

(Electric and Acoustic) Guitars: Elliott Randall

Rhythm Guitar: Jim Miller

Bass Guitar: Gary King

Piano, Organ, Electric Piano: Phillip “Pot” Namanworth

Saxophone, Flute, Clarinet: Paul Fleisher

Drums, Percussion: Allen Herman

Additional Orchestra

Moog Synthesizer: Maurice Kogan

Trumpets: Paul Bogosian, Burt Collins, Alfonse Maiorca, Lloyd Michels

Bassoons: Sanford Sharoff, Mannie Thaler

French Horns: Richard Berg, James Buffington, Donald Corrado, Fred Griffen, Brooks Tillotson

Trombones: Wayne Andre, Randy Maur

Bass Trombone: Anthony Salvatori

Clarinet: Albert Regni

Flute, Piccolo Flute: Katherine Hoover, Seymour Press, Anthony Saffer

Oboe: Sampson Giat, Harry Smyles

Violins: Arianna Bronne, Norman Carr, Harry Cykman, Gayle Dixon, Felix Giglio, Harry Glickman, Emanuel Green, Paul Grotsky, Julius Held, Raymond Kunicki, Morris Lefkowitz, Carmel Malin, Joseph Malin, Michael Markman, Ben Miller, Seymour Miroff, Louann Montesi, Secondo Proto, Alvin Rogers, Aaron Rosand, Frank Siegfried, Herbert Sorkin, Irving Spice, Vladimir Weisman

Violas: Julien Barber, Selwart Clarke, Harold Furmansky, Emanuel Hirsh, David Johnson, Maury Pollock

Cello: Maurice Bialkin, Alla Goldberg, Gloria Lanzarone, Charles McCracken, George Ricci, Ruben Rivera

Double Bass: Samuel Levitan, Barbara Wilson

Harp: Eugene Bianco

Percussion: Gordon Gottlieb, Henry Jaramillo, Howard Kirsch

Track Listing

Side 1:

Heaven On Their Minds

Everything’s Alright

This Jesus Must Die

Hosanna

Pilate’s Dream

I Don’t Know How To Love Him

Gethsemane

Side 2:

King Herod’s Song

Could We Start Again Please?

Judas’ Death

Trial Before Pilate

Superstar

John 19:41

Audio Production Information

Original Release

Produced by Tim Rice and Andrew Lloyd Webber

Production Consultant: Alan M. O’Duffy

Production Coordinator: Tom Morgan

Recording Engineer: Frank Laico

Re-mix Engineer: Elvin Campbell

Orchestrations: Andrew Lloyd Webber

Conductor: Marc Pressel

Reissue

Reissue Produced by Brian Drutman

CD mastering (February 2003) by Mark Omann

Executive Producer: Chris Roberts

Rare footage of rehearsals, the opening night and afterparty and interviews with the cast and creatives of the original Broadway production in 1971.

Historical Notes from a Fan

With unofficial productions banned, the official stage incarnation of Jesus Christ Superstar was now free to go ahead. Tim Rice puts how it went next best in his autobiography: “…in a way, the pirates did us an enormous favor by showing that there was massive potential in Superstar as a live show without the trappings of Broadway and legitimate theatre. On the ‘if you can’t beat ’em, join ’em’ principle (even though he did beat ’em in the end) Robert [Stigwood]‘s masterstroke was to set up his own touring concert version.”

Come summer 1971, 13,640 people crowded the Civic Arena in Pittsburgh for the first concert showing on July 12, breaking the attendance record set there by Tom Jones the year before. The Pittsburgh event kicked off a sell-out concert tour of the US, booked by William Morris. These concerts included a cast of 26 plus 26 musicians, with lighting and costumes but no staging or sets. The original touring company (which included Yvonne Elliman reprising her role as Mary, and newcomers Jeff Fenholt as Jesus and Carl Anderson as Judas) visited 54 locations across the USA and performed the show 74 times.

Indeed, the first/main tour was so incredibly successful — and demand so great — that by the end of the summer of 1971, there were two concert companies simultaneously touring American arenas. The second launched on September 17 in Providence, Rhode Island, unleashed once more by the incomparable Robert Stigwood. (One company sold out two nights at Los Angeles’ famous Hollywood Bowl, taking $200,000 with a top ticket price of $10.) Success breeding success, Stiggie soon added a college touring company, meaning that, at one stage, three simultaneous authorized arena tours were performing the work around the United States.

Variety magazine had quickly predicted that Jesus Christ Superstar would become “the biggest all-media parlay in show business history” upon the concept album’s release. As Rice and Andrew Lloyd Webber had always hoped Jesus Christ Superstar would reach the stage in a fully-staged musical version, there was little surprise that major theatrical centers such as Broadway or London’s West End would be next up for consideration. Given the trajectory of the album’s reception (though it continued to sell in America to the tune of 3.5m copies, Rice characterized the British release as “an absolute dud” at the time), it was even less surprising that the former was the first port to come calling. In October 1971, it was decided, Jesus Christ Superstar would go to Broadway.

The first step was assembling the ideal creative team. There was interest from Hal Prince (producer of West Side Story and Fiddler on the Roof, and producer/director of Cabaret, among others), but Stigwood wasn’t enthusiastic. (Years later, Webber would lament of only receiving the telegram Prince had sent to his parents’ flat seeking to direct and produce JCS after they had signed the rights away: “I could have cried. […] I still wonder how my career would have been perceived in those early days if he had directed it, rather than my theatrical debut being allowed to be turned into a mountain of kitsch that looked like a monument to a demented pastry chef.” More about which momentarily.)

Eventually tapped to helm the musical was veteran theater director Frank Corsaro, not because he’d staged such successful Broadway plays as A Hatful of Rain and The Night of the Iguana, but because he’d turned his attention and direction to classic operas at New York City Opera, infusing his controversial productions with a multimedia aspect. Maybe he’d be just the man for a rock opera. His proposal intrigued the authors: he wished to stage the show simply, using projections and television screens to underline Rice’s themes of celebrity and stardom, with great emphasis on a mix between film and live-action. (Though the authors were pleased with Corsaro’s concept for the look of the show, Rice admits in his autobiography to having had some reservations: “Frank also said he wanted Jesus completely starkers [naked] on the cross. I had my doubts about that one.”)

Pre-production began in earnest. As the authors’ initial choice, he had a huge effect on the shape the production (and the show, as a result) eventually took:

- He chose the creative team (Robin Wagner designing sets, Randy Barcelo costumes, and Jules Fisher lights).

- He asked for alterations in the opera, including suggesting “Could We Start Again Please” (which would give Yvonne Elliman, whom they hoped to reprise her role as Mary, another song, and would soften the mood before the dramatic final scenes) and lengthening the “Trial” scene’s exchanges between Pilate and Jesus. (The score only ran 87 minutes on record, which was rather short by theater standards.)

- He was also involved in much of the casting sessions for the eventual Broadway run, choosing many of the talents who would go on to become deeply involved in the show’s history.

But at the end of July 1971, just as the concert tour was kicking off, Corsaro was involved in an automobile accident and was unable to continue. (Luckily for Frank, he received $40,000 severance pay.) To make the projected opening date, the push was on to find a new director — fast. Sensing that Corsaro was perhaps too respectable a choice for a show that suggested (to him) flash and splash, Stigwood had already been quietly interviewing other candidates, among whom was Tom O’Horgan, who’d staged Broadway’s very first rock musical — Hair in 1968 — and had had a hit earlier in 1971 with Lenny. After initially refusing several times and even accepting other work, O’Horgan was finally offered a very generous deal (including author royalties and credit in the show’s billing which remained part and parcel of the show’s amateur licensing stipulations for decades) that would have been absurd to refuse and signed on the spot.

Not much needed to change within the creative ranks; O’Horgan had worked with Barcelo, Fisher, and Wagner before, and chose to keep them on rather than further complicate the process by asking for a whole new team. However, he did commission new designs (apparently seeing the show as a phantasmagoria, he ordered just that, calling for a larger than life and symbolic approach), and he re-evaluated the initial casting choices in a fresh round of auditions, calling in more than 500 young people (the average age was 21) for castings for the 40 roles over 2 weeks.

Ultimately, Yvonne Elliman (beating out no less a future talent than Bette Midler; see casting director Michael Shurtleff’s book Audition for the full story) and Barry Dennen appeared in the same roles as they had performed on the original album — Mary and Pilate, Fenholt was retained from the first touring company as Jesus, and future showbiz sensation Ben Vereen (then known primarily for being a Broadway replacement in Hair) assumed the role of Judas (following a split vote between Vereen and another candidate, decided by musical director Marc Pressel’s tiebreaker; again, refer to Shurtleff’s book). As three angels, O’Horgan cast three actresses who bore more than a passing resemblance to the Supremes. Anita Morris, later a Tony nominee for Nine, was one of the “Temple Ladies,” while Samuel E. Wright — Simon Zealotes — eventually became the voice of Sebastian not only in the animated The Little Mermaid but also in its many offshoots.

Yet Time‘s music critic Bill Bender spoke for many when he stated, “The last thing I expected to see was a Broadway musical based on the life of Jesus Christ.” Christian Century writer Stephen C. Rose, while acknowledging the “Jewish criticism and mild ecclesiastical controversy,” decided, “I would recommend going to church instead of the Mark Hellinger.” Rose seemed to be just as scandalized by “Broadway’s incredible prices,” at a time when the top ticket was $15. Scalpers, though, were getting double that as soon as tickets went on sale. (Ultimately, the show’s opening gross was $1m-$2m, ensuring immediate success.) The show eschewed the usual but fast-disappearing out-of-town tryout, but it didn’t need such stints to build buzz. Theater writers were already giving JCS a lot of ink. Many Broadway musicals had been featured on the cover of Life magazine, but not nearly as many graced the cover of the more serious Time. JCS snagged both; Life on Oct. 22, 1971, and Time three days later. Time reporter Mary Themo said the performers were quite patient during the Wednesday photoshoot, even though they’d already done two shows that day — though Jeff Fenholt complained a bit because “he had been on the cross too long.” Time writer Timothy Foote was impressed that Webber and Rice were “modest about their talents, grateful for their extraordinary luck, and sensibly reserved about future plans.”

Mayor John Lindsay was among the first-nighters when Jesus Christ Superstar opened at the Mark Hellinger Theatre in New York on October 12, 1971, after only 13 previews. But on opening night, they weren’t the only ones congregating outside the theater. Picketers — Catholics, Protestants, and Jews — made their presence known with placards that sported the title of the show, but with “Superstar” crossed out and “Lamb of God,” “King of Kings” and “Our Hope” scratched in its place. They made it known they weren’t just unhappy that Jesus kissed Mary Magdalene; they didn’t see why the show couldn’t include Jesus’s resurrection, too. A picture of them demonstrating outside the Hellinger was on the front page of the following day’s Daily News.

Even the opening night party at Tavern on the Green was controversial, as then-celebrated syndicated columnist Earl Wilson indignantly sniffed the next day: “Some were in black tie, some in no ties, one in a velvet shirt opened to his navel, one had a rope of pearls, one in a tweed jacket and a coonskin coat, one in jeans and a cap that he never took off… I also saw something in a headband and dress — and a red mustache.” All a good metaphor that times on Broadway certainly were a-changin’. But inside the Hellinger, first-nighters saw where the $700,000 budget went. What seemed to be a show curtain tilted backward to become a desert. Jesus, in an immense shiny train that would have passed muster in a Ziegfeld Follies, made His entrance in an enormous chalice that came from beneath the stage. His enemies then descended from above, on a bridge seemingly made out of desiccated bones. Heavenly stars fell out of a box that was wrapped as a Christmas present. Herod wore elevated shoes, rouge, and lipstick, Pilate donned a silver jockstrap, and those carrying the cross wore football helmets. When Judas hanged himself; he was lifted 40 feet off the stage. Jesus’ 39 lashes were obscured by a sheet, but one on which bloodstains were spattered — all before He was impaled on a gold triangle that emerged from a mouth that bore more than a passing resemblance to Marilyn Monroe’s. As red meteors flew across a backdrop, the song that started it all, “Superstar,” was used for the curtain call. (Time reported that “Things might easily have been worse. For a while, Tom O’Horgan was toying with the idea of a ‘vinyl-clad, hip Christ crucified on the handlebars of a Harley-Davidson.’”)

The only known visual recording of the Broadway show, above, was captured during its appearance on the 1972 Tony Awards, where “The Temple” and “I Don’t Know How To Love Him” were performed.

O’Horgan had told Time, “I don’t think anyone will come out feeling neutral,” and indeed, no one did. Reviews ranged from “Vulgar and slightly ridiculous” (Newhouse Newspapers) to “A spectacular treatment… a remarkably fresh retelling” (Wall Street Journal). The headline for Walter Kerr’s review in the Sunday New York Times was “A Critic Likes the Opera, Loathes the Production.” But drama critics don’t write their headlines. What Kerr did write was that the title page of the program “stresses that O’Horgan has not only directed the production but ‘conceived’ it. It is not an immaculate conception.” Nevertheless, he did allow “There are still two conceivable reasons for going to the Hellinger,” before noting, “the materials are — on their chosen level — worth listening. And of course, you may want to attend simply to see how long a way a lot of bad taste can go.” But the cast got off a bit easier, especially Ben Vereen, who was said to “give an intensely vital performance” (Saturday Review). “His singing, dancing, and acting skills make him a provocative stage presence” (Wall Street Journal) with “considerable talent and limitless energy” (Time). “The evening’s star,” said Harold Clurman.

Then came the deluge of magazine reviews, with headlines like, “Jesus Hits the Jackpot” (After Dark), “Jesus Crisis” (The New Republic), and “Superstunt” (Saturday Review). “A lot of production hokum and stage mechanics,” said Henry Hewes in that last-named publication, echoing what Clive Barnes had said in the New York Times — that it “resembled the Empire State Building” as well as “the Christmas decorations of a Fifth Avenue store.” Probst of NBC said, “It has the feeling of the Folies Bergere and a Cecil B. DeMille movie.” Newsweek called it “a Satyriconized Luna Park of outrageous imagery.”

The result of those slams? Theatergoers then flocked to it as if it were the Empire State Building, a Fifth Avenue store, the Folies Bergere, a Cecil B. DeMille movie, and Luna Park, and sold-out business continued. As Martin Gottfried said in his Women’s Wear Daily review, “Broadway’s disease is a die-hard resistance to anything new” (before he panned the show, too), and as Newsweek reported, “Jesus Christ Superstar is one of the most amazing and complicated media events of the media age” and that “the Broadway opening was the apotheosis of a fantastic success story.”

When the Tony nominations were announced in April, the show didn’t get a Best Musical nomination, losing out to two musicals that many remember (Grease and Follies) and two that less recall (Ain’t Supposed to Die a Natural Death and Two Gentlemen of Verona, which won the prize). Indeed, JCS only scored a modest five nominations (Webber and Rice for score, Vereen for supporting actor in a musical, Wagner for sets, Barcelo for costumes, and Fisher for lighting), and when the Tony winners were announced, no one from JCS got to deliver an acceptance speech, though all but Barcelo would win a Tony or two in the years that followed. But JCS got the last laugh; closing in June 1973, it ran longer than every one of the musicals that won a prize, having lasted 711 performances, which then made it Broadway’s 46th longest-running musical.

That didn’t mean the authors were happy with the resulting production. In later years, writing program notes for a revival, Webber would opine, “I shall never forget the saga of Jesus Christ Superstar on Broadway. Never — in my opinion — was so wrong a production mounted of my work. Even though this brash and vulgar interpretation was quite leniently dealt with by the critics at the time, the public saw through it. The biggest selling double album of all time ran in its first theatre incarnation a mere 20 months. Throughout its entire preview period, I was never allowed to rehearse the orchestra. Looking back 25 years later, I suppose there were pluses. Because the production was so awful, no production of Superstar in the rest of the world was the same, so I had a baptism of fire by a kaleidoscopic gaggle of directors. Most important, I resolved that night that when I got my first opportunity I would start my own production company.” (More about this in Discography entries to come.)

It shouldn’t be too shocking, then, that much like the production had turned out to be less than the authors expected, its cast recording turned out very similarly. The recording of the cast album was scheduled for the Sunday following the New York opening, as per tradition (since there are no Broadway performances of new shows on Sunday). Though they produced the recording themselves (aggravating Tom Morgan, MCA’s East Coast A&R director and coordinator for the project, in the process when he tried in vain to have personal planning meetings), Webber and Rice ran into stumbling blocks at every turn:

- Since the authors felt the MCA facilities were too small, proceedings had to move to Columbia Records’ studio on East Thirtieth Street.

- Webber’s plan to record music and vocals simultaneously — the traditional practice — was scuttled in favor of recording instrumental tracks first and adding vocals later when Decca informed them it had no intention of paying overtime to the entire cast (all union actors come under the jurisdiction of the radio artists’ union when doing an original cast album; each singer is paid one week’s salary for a nine-hour work period that must include an hour break for lunch or dinner, so in theory, five minutes of overtime means another week’s pay, and clocking in at 40 actors and 73 musicians, overtime was a frightening prospect).

- Once the orchestra tracks had been recorded and the cast assembled for vocal sessions, it became clear that all the work could not be finished, so they attempted to finish choral work as quickly as possible to only call in the leads the next day and avoid paying overtime for everyone. Just as the session was winding up, however, a chorus singer called a halt for a bathroom break that unfortunately pushed them into overtime when it lasted 20 minutes. The cost: over $70,000 — more than the original album, which took six months to record compared to the two days eventually afforded the Broadway cast.

Webber, Rice, and Alan O’Duffy, the engineer of the concept album, spent the rest of the week mixing, remixing, and editing the tapes. MCA did not expect the new album to do well if the price was too high, since so many copies of the original had been sold, so it was decided to release a one-record, abridged version in a double jacketed package containing a large assortment of photographs from the show. Ben Vereen termed the record, which had initial sales of $150,000, “sloppily done… nothing but trash.”

Reviews

Everybody is singing hard for their supper

I am somewhat shocked that many people do not care for this recording. Every single singer is giving the performance of their lifetime, singing hard as though their lives depended on it. The orchestration is fabulous. Gary King is possibly the best bassist I have ever heard in my entire life! These are the things that tie it together as an album.

I was but a child when this was released. I had no concept of Broadway itself or any possibility to have seen this in person. And that’s okay. Any criticism of the stage show itself, I cannot speak to. This album however, represents some of the best work ever done.

Great time capsule of Jesus Christ Superstar, 1971!

I had the 1971 8 track tape of Jesus Christ Superstar and played it till I was amazed it would still play! I was having trouble finding the veersion with the cast members and the songs the exact way I loved them. When I read the cast members listed here, I knew it was the right Jesus Christ Superstar. Perhaps I can find a copy in a new format, now that I know what to look for. Thank you so much!