Artwork

Recording Information

Classification: Original London Cast

Year of release: 1972

Language: English

Type: Stage cast

Cast

NOTE: As with the 1971 Broadway cast recording, credits for ensemble vocals merely reflect the liner notes’ report of who was in the cast at the time of recording.

Jesus of Nazareth…………Paul Nicholas

Judas Iscariot…………Stephen Tate

Mary Magdalene…………Dana Gillespie

Pontius Pilate…………John Parker

King Herod…………Paul Jabara

Simon Zealotes…………Derek James

Caiaphas…………George Harris

Annas…………Jimmy Cassidy

Priests…………David Charkham, John Newton, Mark Russel

Peter…………Richard Barnes

The Chorus…………Paul Barber, Pierre Bedenes, Floella Benjamin, Esther Byrd, Derek Damon, Sue Jones Davies, Jean Gilbert, John Kerriush, Diane Langton, Brenda Lawrence, Brian Leeson, Anna MacLeod, Richard O’Brien, Pamela Obermeyer, Sue Potter, Sally Riggs, Annette Roberts, Sally Sagoe, Ronnie Sebalo, Joshua Smith, Larry Walker, Anthony Wood, Geraldine Wright

Orchestra

Lead Guitar: John Girran

Rhythm Guitar: David Whyte

Bass Guitar: Colin Bilham

Piano/Electric Piano: Tony Stenson

Organ/Synthesizer: David Firman

Drums: Roy Jones

Trumpets: Norman Archibald, Dennis Clift, Bert Ezard, Butch Hudson, Peter Owen

Horns: Nick Busch, Robin Davis, Terry Johns

Trombone: David Horler

Trombone/Tuba: Alfred Reece

Clarinets/Bass Clarinets: Jack Brymer, David Lawrence

Flutes/Piccolos: Brian Warren, Averill Williams

Oboes: Ann Boyd, Paul Mosby

Violins: Fred Alexander, Jim Archer, Howard Ball, Peter Benson, Ted Bryett, Richard Bureau, Ben Carpenter, Rita Eddows, Geoffrey Grey, Carmel Kaine, Laurie Lewis, Dennis McConnell, Charles Mckeown, Garth Morton, Alan Peters, Cyril Reuben, Max Salpeter, Charles Verney

Violas: Bernard Davis, Jack Fleetcroft, Harold Harriott, Maurice Loban, John Meek, Steve Shingles, Caroline Sparey

Cellos: Graham Elliott, Eldon Fox, Ted Holmes, Tony Pleeth, Marilyn Sanson

Basses: Chris Lawrence, Laurie Lovelle

Harp: Audrey Webster

Percussion: Eric Allen, Fred Stancliffe

Track Listing

Side 1:

Heaven On Their Minds

Everything’s Alright

This Jesus Must Die

Hosanna

Simon Zealotes

I Don’t Know How To Love Him

Gethsemane (I Only Want To Say)

Side 2:

Pilate’s Dream

King Herod’s Song

Could We Start Again Please

Trial Before Pilate / Superstar

John 19:41

Audio Production Information

A Qwertyuiop Production

Engineer: John Richards

Orchestrations: Andrew Lloyd Webber

Conductor: Anthony Bowles

Orchestral Management: Peter Owen

Cover Design: Carol Smither

Photography: John Haynes, Shepard Sherbell

Recorded at CTS Studios, London

Historical Notes from a Fan

Let us set the scene: it is now 1972. A year ago, Jesus Christ Superstar had just reached Broadway as a spectacular, flamboyant, over-the-top, eye-popping extravaganza. And neither the critics nor Tim Rice and Andrew Lloyd Webber were won over by director Tom O’Horgan’s outrageous sensory-assaulting production. In later years, writing program notes for a revival, Webber would opine, “Looking back 25 years later, I suppose there were pluses. Because the production was so awful, no production of Superstar in the rest of the world was the same, so I had a baptism of fire by a kaleidoscopic gaggle of directors.” As Rice described the same period in his autobiography, “Robert [Stigwood] had decided that he would not entrust the London show to O’Horgan, and it was extremely useful for us all to see other ways it could be done […] Because of the general lack of confidence in the O’Horgan version, all of these were brand new productions, and none bore any resemblance to the Broadway show.”

Further, after the success of the Australian production, it was decided to entrust the directing reins on the West End run to its helmer, Jim Sharman, who accepted on the condition that his set designer, Brian Thomson, accompany him (as he says in his autobiography Blood & Tinsel, “[his] spectacular dodecahedron, tubular elevators and floating ramps had contributed mightily to the Australian production’s success”). As Tim Rice puts it, “I took a great liking to Jim and although I had a few reservations about some of his ideas, I was more than happy when Robert offered, and Jim accepted, the London job. Jim stated before the Sydney show even opened that he would not simply repeat himself in the West End.” Not that this stopped anyone from doubting he could do the job: in his autobiography, Sharman would later recount the tale of an occasion following the opening spent “nursing a drink in the Soho pub next door to the Palace Theatre, sitting with Brian Thomson” as the pub’s owner (“a cheerfully waspish old theatre queen”) told them, “When we heard we were getting the Australian production… well… my dear… you can imagine… we all just roared with laughter!”

Aside from frank negative assessments of Australia’s cultural credentials from the British public circa 1972, Sharman was keenly aware of what else he was up against: “Superstar began its life as a hugely successful recording, yet it had faltered on stage in Paris and on Broadway. It was challenging and unconventional, and there were issues of taste and a degree of theatrical condescension surrounding the idea of a biblical rock-and-roll opera. I liked it and took it seriously […] Robert agreed to my choice of designer, and Brian and I set off to create a new production in London.” He was also serious about taking an entirely different approach to the show than he had in Sydney: “…influenced by discussions with Robert, Andrew, and especially Tim Rice, [we] did Superstar the great service of treating it simply. We allowed for a little spectacle, though much less than in the overblown Broadway version or our more flamboyant Australian staging. From the concert version, I retained the direct-to-audience communication of songs and interwove this with a more realistic narrative in the thematic scenes. Influenced by Pasolini’s film The Gospel According to St. Matthew, the London version had a starker, more human dimension.”

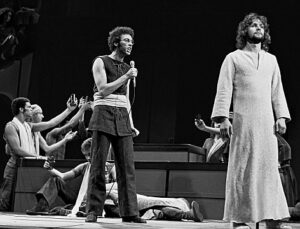

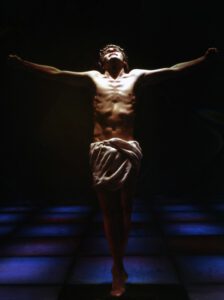

Rice recalls what changed in terms of design: “Jim’s show was very different from his Australian production. He ditched many of the space-age trappings of his first effort, including the huge plastic dodecahedron that had slightly cramped his room to maneuver in Sydney. The set […] was stark and bare; the central playing area a large box with a slightly raked, lit floor [Sharman describes it as a “vast steel and glass ramp”] surrounded by three walls, wide and high, over which members of the chorus clambered throughout the evening. A Piccadilly Circus display of lights flashed up occasional words of information such as ‘Jerusalem, Sunday.’ [Sharman calls it an “electronic news board urgently flashing details of time and place.”] The simplicity of the basic staging generously allowed the words and music to become the main driving force of the story, but there were many moments of great visual impact, primarily through the movements of the swirling chorus, with lights, dry ice, colorful banners and artful choreography (by Rufus Collins).” Sharman makes additional mention of “an elegant colonnade of floating pillars” and also adds, “New York lighting whiz Jules Fisher created visual marvels, including a nuclear cloud swathing a Jesus seemingly crucified midair…” (Rice called it “spectacular but restrained” and remembers that “Jesus’ cross rose from the depths.”)

A small change in dramaturgy also occurred which Sharman opines was “a less obvious factor in [the production’s] success,” though no less important a factor: “…the placement of the interval […] was never specified, and varied from production to production, but I felt that the scene in the garden of Gethsemane, climaxing in Christ’s great ‘Why me?’ anthem, sat at the heart of Superstar and was the logical climax of Act One. By placing the Gethsemane aria just before the interval and leaving the audience to ponder Christ’s deeply human dilemma, and have them return to […] the showdown between Jesus and Judas […] opened the bleeding wound at the heart of this modern passion play. The incision became a door through which the audience could enter and deepen their engagement with this rock-operatic drama of love, sacrifice, and betrayal.”

(Though Rice recounts in his autobiography that “Andrew and I always felt that the first act ended at [‘Damned For All Time / Blood Money’],” an ending more familiar to many American readers and listeners of the original album, he nonetheless acknowledges that “in the majority of the stage productions around the world, the break seems to have worked better after the Last Supper and Gethsemane scenes.” Indeed many productions in the UK, but especially in London’s West End, have followed this placement of intermission, and as per its Playbill, the original 1972 Los Angeles production did likewise. That said, many more productions have placed the intermission where it was on the original album and not suffered for the choice.)

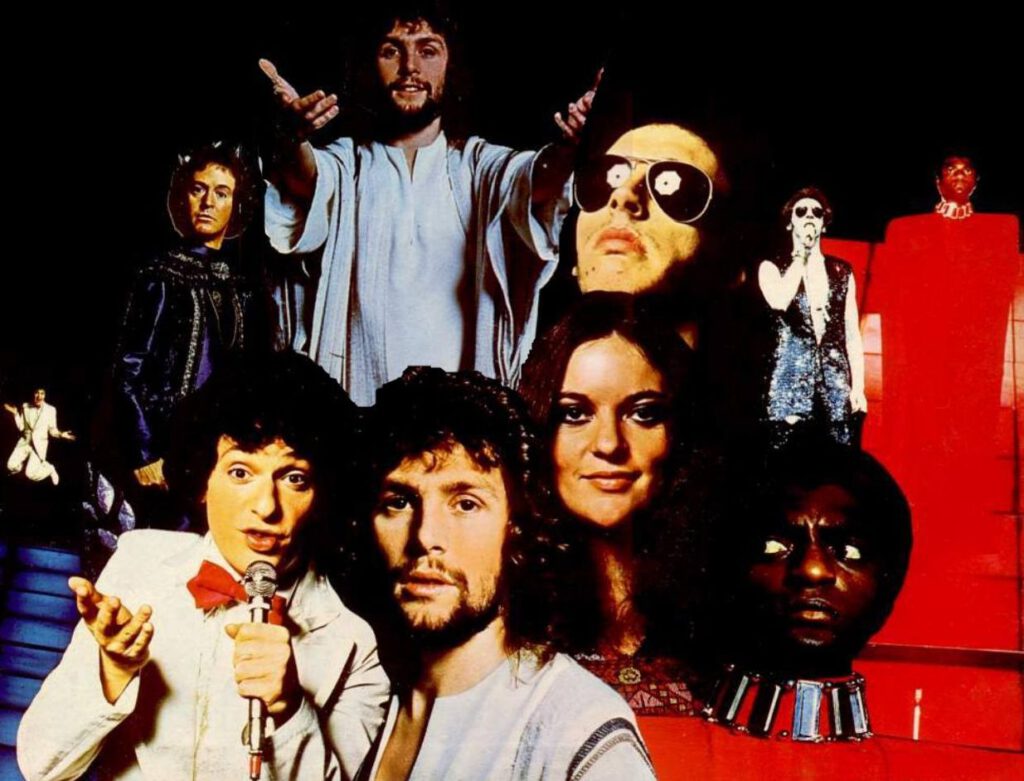

Casting proceeded speedily. Paul Nicholas, plucked from the London production of Hair (where Sharman also met choreographer David Toguri and actors Tim Curry and Richard O’Brien [the latter ended up in the JCS chorus], all later of Rocky Horror), assumed the role of Jesus opposite the less established Stephen Tate as Judas. John Parker played Pilate, and Paul Jabara, remembered by Rice as “a crazy American based in London,” was cast as King Herod, turning in what Sharman called a “brilliant” and “memorably asinine” performance. As Rice recalls, “…the role of Mary eventually settled upon Dana Gillespie, after the original leading lady selected proved unsuitable — not untalented, but not right — and Dana was promoted from the chorus at the eleventh hour during previews.” Tim further mentions that Dana, who Sharman remembers as “vocally and physically impressive,” “had achieved a certain notoriety via her appearance in Bob Dylan’s documentary of his 1965 tour of Britain.”

There were other hiccups during previews, as Rice acknowledges: “I recall a panic over costumes which were changed radically from first-century Oxfam to timeless desert chic with about one preview to spare [… and] a last-minute wobbly from Andrew when he told Robert with three days to go that the whole enterprise was doomed and that he was removing his score. Once again, I found Andrew’s pessimism catching and as we drove out to Robert’s Stanmore mansion one night to plead the case for total abandonment, even I was briefly convinced that we were heading for irretrievable disaster if we didn’t send Jim and his cast packing the next morning. Robert dealt with our ludicrous quest with tact, calm, and a lot of champagne.”

(Good thing issues on opening night weren’t considered an omen that their misgivings were correct. Recalls Rice of the crucifixion sequence, “…on the opening night […] a safety clicked into action for over a minute, trapping Paul on the cross in the basement. This delay seemed like an hour to conductor [Anthony Bowles, retained from the Paris production], orchestra, and cast, desperately holding on to one note of anguish which they did not have to act to convey, and to two panic-stricken authors standing at the back of the stalls. Eventually, the contraption lurched into action just before we felt we should rush onto the stage to apologize, or rush out of the Palace altogether, by which time most of the theatre had been filled with smoke that had been pumped out for much longer than intended. If anything, the delay added to the dramatic tension of the climax of the show.”)

What may have helped the tact, calm, and champagne go down easy was the fact that the time finally seemed right for JCS in the UK. While the UK reaction to the original album had initially been cool, the momentum of the international success of the show had finally begun to penetrate; by the time producers were creating London’s production there was no shortage of pre-sales. Indeed, when the show opened at the Palace Theatre on August 9, 1972, it was the beginning of an almost decade-long run, clocking in at 3,358 performances and plenty of critical acclaim. (Recalls Sharman, “…the leading theatre critic of the day, Harold Hobson […] trumpeted in the Sunday Times, no doubt to the relief of the publicist: ‘The kingdom of heaven will open to receive this production.’”) Upon the show’s West End closing in 1980, the first UK tour (produced, as all early runs were, by Stigwood in association with MCA, and by arrangement with David Land) opened at another Palace, this one in Manchester, on August 21, 1983, touring to similar success.

Among the many factors above that Sharman feels helped the production become such a hit, JCS Zone would be remiss if it didn’t tweak one of our experts, Mark Jabara, with this memory from Jim’s autobiography: “A Texan producer whom I met soon after Superstar opened in London, a large goatee-bearded man with a generous laugh, wanted to buy the production. It wasn’t for sale. However, he loved Superstar and had seen every version. In passing, he observed that mine was the only production that left a window open to the possibility of faith. In his opinion, this was part of its appeal to the public.”

Regardless of what factors played the biggest roles in the London production’s success, the salient point is that it was successful, grossing $12.3 million and becoming the longest-running musical in West End history at the time, proving that the stage version of JCS, much like the original album, did have legs despite the adversity it faced. As an album, however, it misses the mark. Though “Herod’s Song” works wonderfully in an uptempo treatment, “Trial Before Pilate” is nothing short of remarkable, and the lead guitarist in the pit wakes everyone up by deciding to dust off his Wah-Wah for the duration of “Simon Zealotes,” this recording isn’t one to walk a mile to own for money. Far more lyrical than the typical screaming-Jesus approach, Bowles, as conductor, seems to insist upon sane theatrical interpretations of the roles, delivered with clipped British accents, dampening down the orgasms and hysteria that the rock fraternity wallows in. As Vinyl Vulture puts it in its terrific (now out-of-print) feature on the early recordings of JCS, “Well, it had to happen — the luvvies got involved, JCS made it to the stage, and […] [i]t’s no surprise that the temptation to ham it right up cannot be resisted for even a second. […] Thesps, eh? Rubbish.”

Reviews

First musical

With my dear friend Vera we came from Amsterdam to see the show. It made a huge impression an experience we will never forget.

London 1973

I took my mum to see this in 1973 for her 36th birthday. She was a young mum, I was 18. I was sharing a London flat with Diane Brown, a student from the West Country. Diane’s boyfriend, I beleive his name was Ritchie Black, was a lighting engineer on the show and he got us tickets for good seats at the front. I think the theatre was on Shaftesbury Avenue, or at least close by. We both loved the show. It was wonderful, so exciting, and possibly the best show I ever saw. Its very interesting to read about it now. I lost touch with Diane. It would be marvelous to track her down after so long. I often wonder what happened to her and Ritchie.