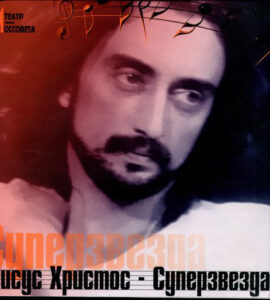

Artwork

Cast

NOTE: We thought it necessary to account for the unusual listing of two performers alongside certain roles. This is because two versions of this cast album were released: one with the principal cast, the other featuring the alternates or understudies for some of the roles. At least one review indicates a later re-release mixed tracks from both versions, with some songs featuring the principals and others the alternates. Your copy may vary!

Jesus of Nazareth…………Oleg Kazancheev

Judas Iscariot…………Valery Yaremenko

Mary Magdalene…………Lada Maris / Olga Mokhovaya

Pontius Pilate…………Boris Ivanov

King Herod…………Sergey Prokhanov

Simon Zealotes…………Eduard Stepin / Vadim Prodanov

Caiaphas…………Vyacheslav Butenko

Annas…………Leonid Senchenko

Peter…………Andrei Mezhulis / Neil Kropalov

Additional Vocals…………The Architects

Orchestra

(Electric & Acoustic) Guitar: V. Golutvin

Bass Guitar: E. Kazantsev

Piano, Organ: S. Nefedov

Trumpet, Percussion: A. Chinenkov

Violin: V. Petrov

Drums: Y. Kitaev

Drum Programming: V. Savin

Audio Production Information

Translation by Yaroslav Kesler

Musical Direction by Alexander Chevsky

Artwork: Boris Blank

Track Listing

NOTE: For this particular production, as outlined in the next section, a lot of changes were made to the songs and the order in which they were performed, both on stage and this album. Some were cut and given an alternate title; others were removed completely or re-arranged in some way. The following translated tracklist in no way indicates that any titles the reader recognizes would be completely the same as what they know if they were to hear them; it’s merely an indicator of which moment in the traditional score the scene best approximates. Any titles you don’t recognize as standard JCS, which are marked below with an asterisk, reflect additional scenes.

Act 1:

Uvyertyura (Overture)

*Nagornaya Propoved’ (Sermon On The Mount)

Nebom Golovy Polny (Heaven On Their Minds)

Chto Za Shum? (What’s The Buzz / Strange Thing, Mystifying)

Kolybel’naya Magdaliny (Vse Khorosho) (Everything’s Alright)

*Zabvenie (Oblivion)

Zagovor Kayafa (This Jesus Must Die)

Osanna (V’yezd V Iyerusalim) (Hosanna / Simon Zealotes / Poor Jerusalem)

Son Pilata (Pilate’s Dream)

Izgnaniye Iz Khrama (The Temple)

Kaleki (Cripples)

Kak Yego Lyubit’? (Duet Magdaliny I Iisusa) (I Don’t Know How To Love Him)

Predatel’stvo Iudy (Damned For All Time / Blood Money)

Act 2:

Taynaya Vecherya (The Last Supper)

Gefsimanskiy Sad (Moleniye O Chashe) (Gethsemane)

Arest (The Arrest)

*Pilat I Kayafa (Pilate And Caiaphas)

Pilate I Iisus (Pilate And Christ)

*Pilat I Magdalina (Pilate And Magdalene)

U Tsarya Iroda (King Herod’s Song)

Raskayaniye I Smert’ Iudy (Judas’ Death)

Sud Pilata (39 Pletey) (Trial Before Pilate [39 Lashes])

Zagrobnaya Ariya Iudy (Superstar)

Epilog (John 19:41)

Historical Notes from a Fan

As discussed on the page for Soviet jazz/rock band Arsenal’s album which featured highlights from the score, Jesus Christ Superstar had a tough road behind the Iron Curtain from the day it began. While JCS is one of the most famous examples of rock opera, and left an enormous impact at the beginning of the Seventies, everywhere else, it was received much differently in the USSR. For one thing, the Eastern bloc viewed it differently from the West for political reasons: in the country where communism reigned triumphantly, a musical based on the last days of the founder of Christianity did not blend well with official atheistic ideology. (Ironically, while JCS was popular in the West because religious authorities from the Catholic Church on down passed judgment on it for its “blasphemous” views, it was “alternative” and a novelty to Russian audiences purely because it dealt with a religious subject, to begin with.) For another, rock music was verboten by the local authority for being a corrupt Western influence.

It shan’t be much of a surprise, then, that JCS was enthusiastically embraced by the rock underground in Russia, both because of its innovative sound and its nonconformist storyline. Though the first Russian language adaptations ultimately appeared later than such Western locales as Sweden and Spain, they certainly made up for lost time with quantity. As of this writing, there have been at least five Russian translations of JCS, three of which have been recorded or performed live.

This particular recording comes from the first theatrical presentation of the piece, by Teatr Im Mossoveta, which opened on July 12, 1990. Its translator/adaptor, Yaroslav Kesler, had developed his own unique treatment “based on” the show well before this and had begun a couple of years before to search for a suitable venue. After hooking up with stage producer Pavel Chomsky and director Sergey Prokhanov (star of such films as Mustached Nanny and artistic director of Moscow’s Luna Theater), a production began to take shape, incorporating established Russian actors, a vocal group called The Architects, and — in the orchestra pit — members of popular rock band SV. It took five years before they recorded and released a cast album, which reviews suggest was somewhat shortened from what was heard on stage.

Kesler’s version of JCS was unique in several respects. He described it as “a peculiar combination of a rock opera, an Orthodox reading of the Gospel, and traditional Russian acting techniques,” which apparently meant scarce adherence to the original. Some moments were edited and re-titled; others were removed completely. A few scenes were expanded, or newly written to Andrew Lloyd Webber’s melodies, incorporating material from the “novel within the novel” in Bulgakov’s Russian classic, The Master and Margarita. What was there at the outset was massaged to more closely resemble the New Testament; a rendition of the Beatitudes was inserted following the Overture, and the apostles’ fierce disagreement with Jesus in “Strange Thing, Mystifying” — “No you’re wrong, you’re very wrong!” — instead became a fervent declaration of love and belief in him. On a similarly traditional note, Kesler’s script offers Judas no sympathy, nor, indeed, dignity; he’s a sniveling coward, clueless, abusive, and useless except to betray Christ. He’s barely strong enough to keep his clothes on, at times rolling around on the floor and foaming at the mouth. Christ, on the other hand, wears gleaming white robes, which almost seem to shine in a world made up of stone and leather. Mary Magdalene, for her part, starts off a tramp in the first act and becomes a wise, sensitive mother figure in the second.

Coming as it did following the fall of the Soviet Union, the show became a sort of commentary on the ambivalence of life after the revolution: Jesus’ teaching was presented as a revolution that fell apart even before his death because his “inner circle” (in leather “punk” costumes, apparently regarded as a throwback to the rebellious spirit of the Sixties and Seventies) couldn’t agree what it was about. In one (added) scene, Simon Zealotes, whose style of speech and costume come to resemble Trotsky, and Judas argue about the dialectics of revolution; elsewhere, the Sanhedrin (who wear police helmets and carry batons) resemble the Politburo, while Pilate’s translated lyrics quote Stalin — explicit manifestations of communism. In the end, the infighting becomes so serious that seemingly everyone betrays Jesus: Simon Zealotes argues at one point that the revolution will be much better off with a martyr and subsequent cult of personality, especially since Jesus seems to be losing heart, while in another scene, Mary Magdalene assures Pilate that if he will set Jesus free, she’ll force her master to retire from politics. Most confusing of all, the crucifixion scene was marked by the appearance of part of an Orthodox icon lowering from the rafters, following which, moments later, Christ appeared fresh as a daisy and decidedly un-crucified, riding a motorcycle with Mary Magdalene’s arms around his waist.

Though the music was close to the original from the viewpoint of arrangements and orchestrations, the very loose adaptation easily drew ire from some critics, with Petr Tiulenev declaring, “Mossovet’s staging of Superstar is worse than the Western original from an artistic point of view and its spirit does not correspond to it at all.” Others were more sympathetic, such as Louis Train, who contended (of a later run; the production has continued at the Mossovet a few months out of every year since 2006) that “Webber and Rice used religion to celebrate counterculture; surely Pavel Chomsky can use counterculture to celebrate religion.” As with the original, the quality must ultimately lie in the eye of the beholder.

Reviews

Best Russian version and probably beats the original in some aspects

Best Maria Magdalena ‘how to love him’ of all versions including original. There is a blend of pop, musical and folk in her voice which is quite amazing. Words are very well pronounced and singing is effortless. There is a grand finale of the track which leads to tears. It would be hard to appreciate the quality of the lyrics and delivery by Olga Movhovaya without knowing Russian. What is also impressive is that the second performer Lada is also very masterful and even hard to tell them apart. The entire show is indeed not a copy but an alternative version and as it often happens some parts came out better than the author’s.